This seminar took place in the Horton room in the Bodleian’s Weston Library on 1 April 2019. The seminar was funded by the Faculty of Humanities at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, which is my home institution. For the spring term I am doing archival work in Oxford, and I am extremely pleased and grateful to have been given the opportunity to arrange a seminar at one of the world’s most important libraries.

When planning the seminar together with Giles Bergel and Una Mcllvenna we were aiming to put together an interdisciplinary group of scholars. Present at the seminar were thus scholars and librarians from history, media history, folklore studies, musicology, Renaissance studies, Nordic studies and literary history. Geographical diversity was also achieved and we managed to discuss news balladry as it was conceived in eight European countries: Britain, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Germany, Norway and Sweden. Although we tried to refrain from mentioning the dreaded B-word (that one that rhymes with ‘exit’) we were all painfully aware that the Euro component had become infused with new tension and drama since we started planning the seminar about 8 months ago. And although we are aware of the limitations of historians to change the course of contemporary politics, we couldn’t help but feel that our theme for the day – what connects the news ballad across the European borders – was timely and appropriate.

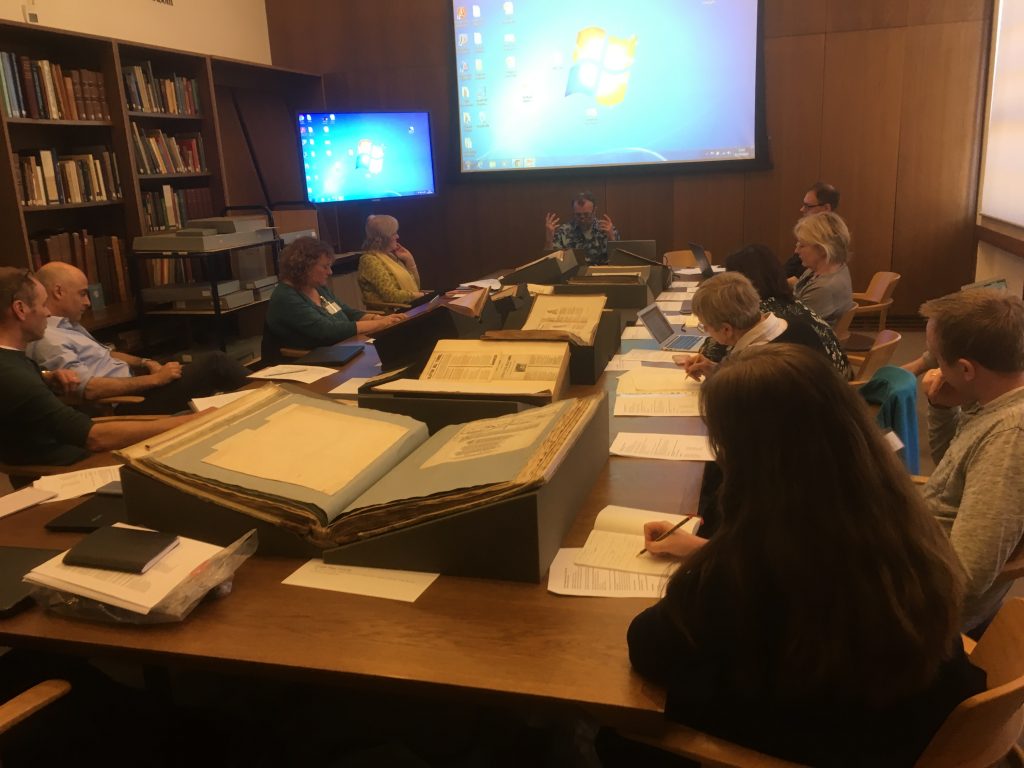

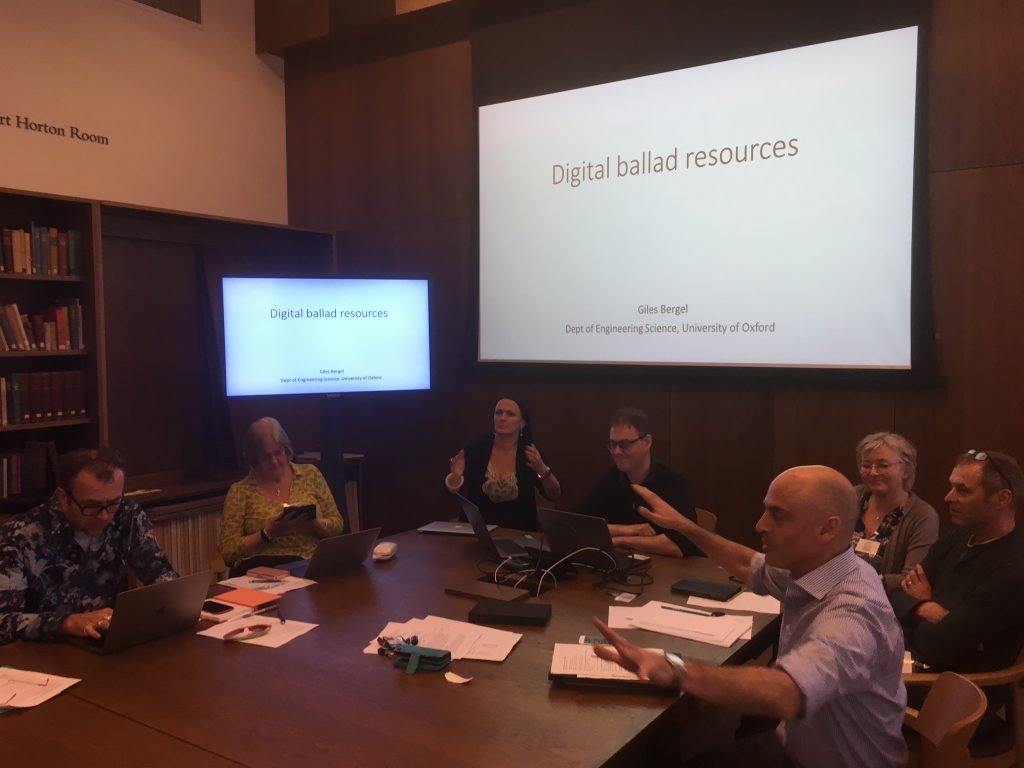

The seminar took place at the Weston library which is part of the Bodleian library. This is a special collections library with restricted access and strict security measures. We were allowed to have our seminar in the Horton room, a magnificent but small room where we were able to fit in 22 specially invited participants. Shown here is Dr. Alexandra Franklin who is the coordinator for the Centre for the Study of the Book at the Bodleian, and who kindly allowed us to arrange the seminar here – and to see some of the news ballads from the Bodleian collections.

A comparative approach to the European news ballad

The main research question that formed the basis if this seminar was as follows:

Was there such a thing as a pan-European genre of news ballads in the period 1500-1900, and how can the search for the common denominators of this prominent genre help us understand the place of ballads and news within a shared European cultural heritage?

In my introduction I asked whether it makes sense to, on the one hand, look at news ballads which offer accounts of the same event– i.e. those that are local news in one place but which travel to become foreign news in other areas – and those that are comparable on a genericlevel, i.e. those that deal with the same kindsof events, for example fires, shipwrecks, earth quakes, etc. The latter approach – a generic comparison – might be the way forward in comparative studies of the European news ballads, since by studying them en masse we might be able to see the remarkable genericsimilarities across time and space: As is the case with much popular literature, the key to understanding the cultural role of these texts might be to uncover what unitesthem, and we are much more likely to discover their shared qualities if we look beyond our national borders and embark upon a grand tour of Europe.

The first approach, comparing the same event, is obviously more complicated: although we are confident there exist hundreds of news ballads reporting on the same event across Europe, particularly if we start investigating political ballads conveying news of warfare and great battles, the examples are difficult to find because they require multilingual skills as well as access to digital resources, some of which are behind expensive pay walls. But multilingual comparisons of news ballads are also difficult because news ballads are by their very nature bound to time and space, the national and the local. This also means that the news ballad shares with the newspaper a certain ephemerality or that it is at least a little less likely to have been treated as a collectible item than the more timeless ballads that have been passed on in folklore: that which is news will quickly also become old, stale news. This postulation was, however, challenged throughout the day, as we were discussing whether the news ballad was a vehicle for opinion and moral sentiments rather than news: we were open to the explosion of the category that was our starting point.

This seminar was a testing ground to see whether it is worth embarking upon a grand tour of Europe in search of news ballads, and to ask what the best travel routes are; what kind of dangers of generalizing one might encounter when comparing national traditions, and, of course, whether comparisons can bring us closer to understanding aspects of a shared European cultural heritage that has not yet been thoroughly investigated. The positive energy in the room and the intensity of the discussions throughout the day, suggested that we are more than ready to embark upon such a Grand Tour – and that we need to do this together.

Una Mcllvenna (University of Melbourne) was our keynote for the day: She is one of the few scholars who has ventured on this tour already, via several invaluable articles where she applies a multilingual and long durée approach to European news ballads. In her talk she gave us some of the highlights from her studies, and revealed the exhilarating and troublesome trawling of European ballad archives so as to chart the importance of news-singing across the borders.

Steve Roud and David Atkinson gave us a glimpse of their new edited book, Cheap Print and the People: European Perspectives on Popular Literature which is in its final stages of publication, and to which several of the seminar participants are contributors. Steve made a strong case for including the East in any future pan-European study, and that this inclusion would undoubtedly lead to the discovery that differences between cheap prints across Europe are more prominent that the likenesses – not least when it comes to the state of the fields within each country. Working with the book was, according to the editors, a humbling experience, in the sense that they discovered to what extent Anglophone researchers has benefited from decades of scholarship and digitization, whereas many other scholars – notably in eastern Europe and in Scandinavia – have a very long way to go with the mapping of national traditions of cheap print and popular literature. This book, soon to be published, will certainly be an essential starting point for multilingual studies of the future.

News, no news – or fake news?

One of the most important threads of the day was the challenge to the actual terminology which has shaped, and continues to shape, our studies of balladry, and our asking whether news ballad is actually a valid term for this genre. From a Scandinavian point of view, the news ballad (“nyhetsvisen”) can be defined in the following way:

A ballad which reports and comments upon a current event by providing the time and place as well as details of the event on the title page and/or in the text itself.

The definition can probably be applied to news ballads in other European countries – but this seminar was also an occasion to probe the definition and the terminology: to discuss whether we should talk about “news ballads” primarily as journalistic or literary texts, and whether their main function was to report, instruct, comment or entertain.

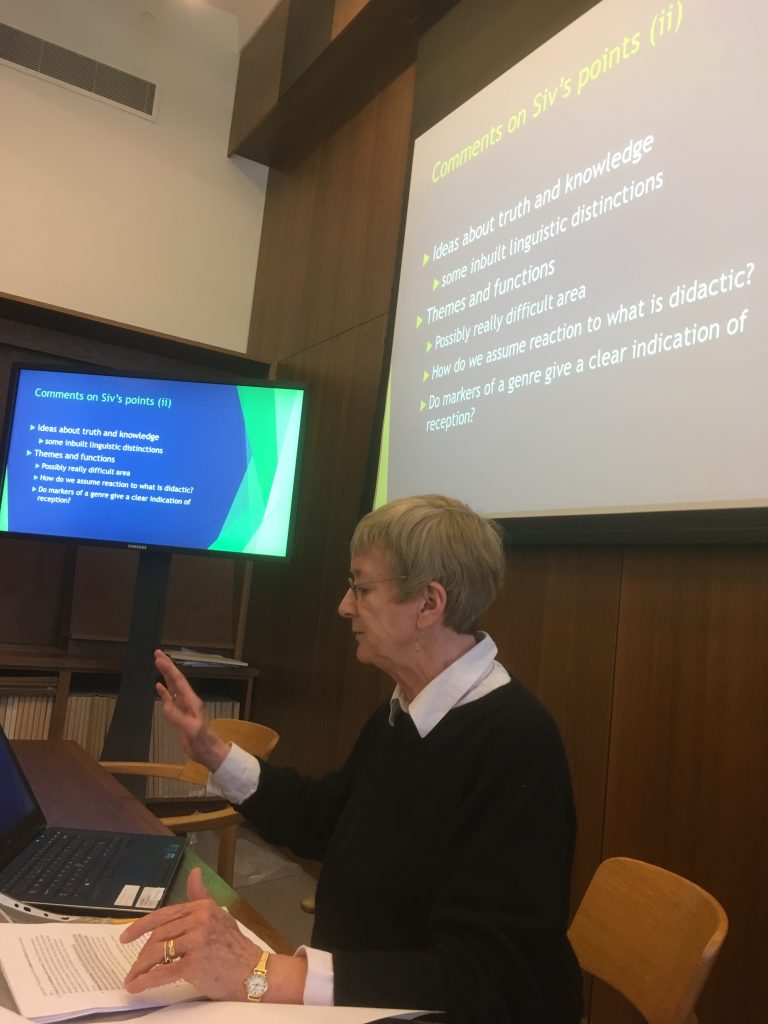

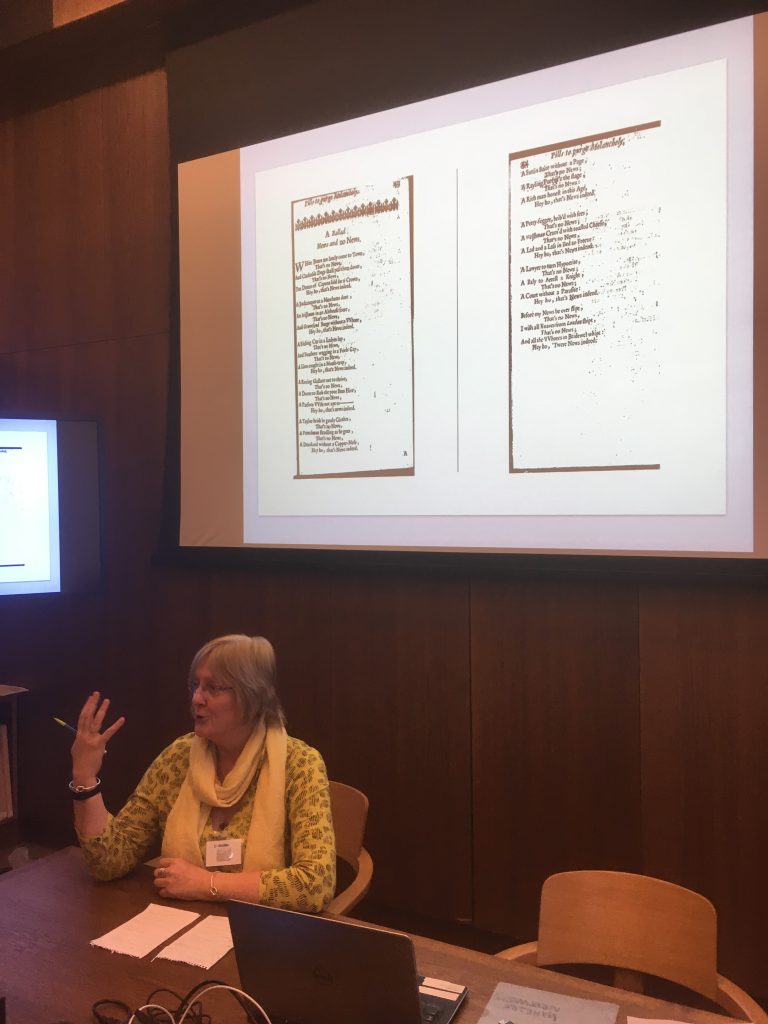

The critical approach to the concept of “news ballads” was very much at the heart of the presentation by Angela McShane (Wellcome Trust, London) who has written several ground breaking articles where she questions the validity of the term, and points to the anachronistic approach to a genre which was essentially more poetic than journalistic. McShane prefers the term “political ballads” and suggested we should scrap the term “newsworthy” and rather talk about “ballad-worthy”. Joad Raymond (Queen Mary University, London) likewise, argued the case for seeing the ballads differently from newspapers: ballads are not primarily a news form; not only do they lack the periodicity and “seriality” of the newspaper; they also differ from printed news forms in narrative terms, and the text is a vehicle for the music. Raymond pointed to the importance of considering “bundling” and that we always need to supplement the study of ballads with knowledge of context and of other texts alongside which they were created. Una Mcllvenna asked us to consider how many ballads express a form of nostalgia rather than news: many ballads which may look like news vehicles fresh from the press are actually reporting on events taking place years after the event. In his talk, David Hopkin (Hertford college, Oxford) pointed to an absence of news ballads (“canards”) in France, and wondered whether this was to do with the lack of diversity in the uses of melodies in France.Alison Sinclair (University of Cambridge) asked whether Spanish news ballads are different from news balladry in other countries, in part because of the spread and density of the Spanish population in the early modern period and eighteenth century.

On the other hand, there were examples throughout the day, not only of how ballads could and would convey news, but also how international news were spread via ballads. Jeroen Salman (Utrecht University) referred to the 1755 Great Lisbon Earthquake as an example of a major event that “made it” in Europe via ballad prints in both the Low countries and beyond. Salman also drew our attention of the influence of the Reformation and other religious movements to understand the spread of cheap prints such as ballads in the early modern period. There was agreement that news ballad had multiple functions within most European countries: the capacity to stir emotions and offer comfort, often in religious terms, was a common denominator for the European news ballad; so too was the commercially inclined focus on entertainment. But for the Norwegian ballads, for example, we cannot rule out their ability to have served as carriers of news: given the very late development of the newspaper in Norway (in the 1760s), the skilling prints offering very detailed and accurate reports on news – particularly on ship wrecks in small places – might have had an informative function prior to the establishments of the newspaper.

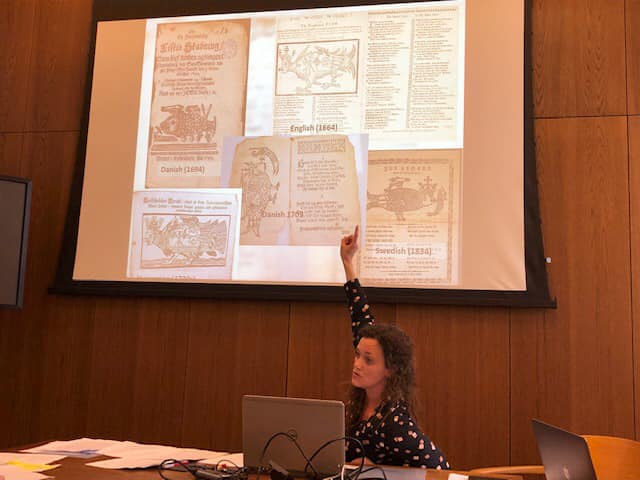

The «prophetic fish» was seen in at least 7 different European beaches in the seventeenth- and eighteenth centuries – according to «true» reports in news ballads.

One important insight that we learnt from the seminar was that we need to be careful about giving prominence to the “accuracy” of ballads. Several of the seminar delegates wanted to abandon the search for accuracy in balladry altogether – particularly because of the capacity (and perhaps even inherent propensity) of ballads to offer fake news “arranged” as factual news. In his talk, David Atkinson showed us examples of British ballads presented as true news reports – complete with time, place, names and details of the event – which he has found to be fake. David Hopkin pointed out that the French term for news ballads (“canards”) had acquired the meaning “false news” already by the sixteenth century. Both Una Mcllvenna and myself showed the example of the prophetic fish – a “pan-European” political and emblematic ballad which was, in some countries, presented as a news item – and I asked whether fake or fantastic news conveyed in ballad form might have been both more enduring (i.e. more “collectible”) and more prone to be shared across European borders because of its sensational qualities. Recently, scholars have proven that fake news is shared six times as fast as factual news; it is worth considering whether this applied to the earlier period too.

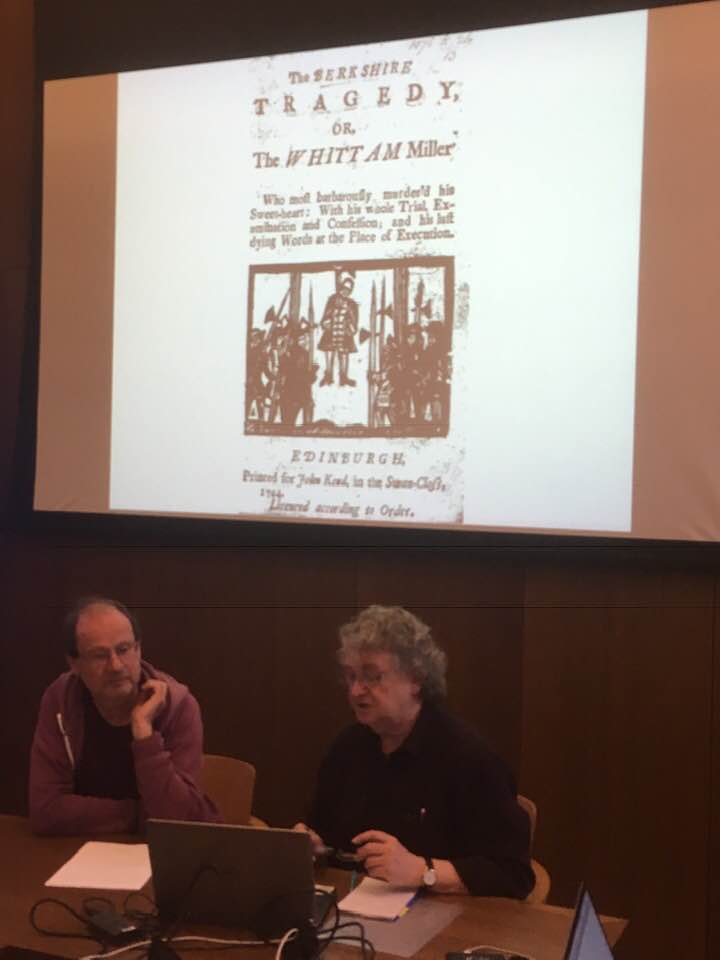

Crimes, murders, executions!

Not surprisingly, crime was a thematic echo throughout the presentations and discussions of European news ballads. Crime has been something of an obsession for ballad authors and audiences across time and place. David Hopkin mentioned that crime is a dominant theme in French canards; Anne Sigrid Refsum (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) talked – and sang! – about the nineteenth century Norwegian hero-criminal, the notorious Ole Høiland, whose career resembles that of Robin Hood. When finally caught by the police, Høiland, unable to cope with his long prison sentence, committed suicide, but many other criminals across Europe were, of course, made to pay for their crimes with their lives – and ballad authors eagerly followed them to the gallows. Execution ballads, then, are among the most popular genres of the early modern period. Karin Strand (Centre for Swedish Folk Music and Jazz Research) showed how female Swedish women committing infanticide were characterised in ballads – and how the narrative voices of the “repentant” child murderesses changed throughout the period. Alison Sinclair showed us examples of pliegos sueltos (Spanish crime chapbooks) and pointed to some important likenesses and differences between Spanish and English execution ballads. Angela McShane also pointed out the prominence of execution ballads (alongside military ballads) in the broad landscape of political ballads in early modern England, and ballads on executions form an essential part of Una Mcllvenna’s several multilingual, long durée studies and digitisation projects.

Was the news really sung?

One issue that was repeated throughout the day – like a basso continuo – was the fundamental question of whether the news ballads were actually sung? The posing of the question is in itself controversial, since the performative aspect is essential to our understanding of the unique place of balladry in oral culture. From an Anglophone point of view there is plenty of evidence of ballad singing throughout the early modern period, and this goes for both news ballads and more traditional “timeless” ballads. In his presentation, Oskar Cox Jensen (Queen Mary University, London) gave examples of thrilling nineteenth-century accounts of ballad singing as a form of urban disturbance. Cox Jensen has found newspaper reports and court documents to show how one ballad singer of the 1860s was arrested for disturbing the public order with his ballad on a notorious case of a scandalous elopement case. Cox Jensen also sang a couple of stanzas of the ballad in question. Jenni Hyde (Lancaster University) is an expert on mid-Tudor ballads and she pointed out how an understanding of ballad culture in this early period relies on our capacity to understand the role of oral transmission and to gain knowledge about the tunes. Alison Sinclair noted that many of the Spanish ballads do indeed refer to a known melody.

Angela McShane

On the other hand, Matthew O. Grenby (Newcastle university) questioned whether the political ballads that he has investigated – election ballads used as political propaganda in the late eighteenth century – were actually sung or whether they functioned “merely” as propagandistic print items: Grenby has found many ballads which use footnotes and other print features that we typically associate with print and reading culture rather than oral culture. Moreover, we found out that the prominence of ballad singing might differ across Europe: From Sweden, for example, Karin Strandinformed us that there are speculations amongst scholars whether the late nineteenth-century “skilling ballads” were more important as print items and were less part of an oral and musical culture at the time: Choruses are unusual in the Scandic material, and a great many of the news ballads from the period give emphasis to prose reports and (as with the election ballads Grenby talked about) they have footnotes, suggesting that they were printed mainly to be read. The absence of contrafactum in the Swedish material is, we agreed, less stable evidence, since this might very well have been due to the melodies and texts being well-known, or that one could just apply one’s own melody. Una Mcllvennatold us that in Italy we rarely find any tune indication, but that Italian ballads had other means of suggesting melodies, such as metrical structure.

Both Jenni Hyde and Una Mcllvenna reminded us that the news ballads of the early modern period were multi-sensory: they not only appealed to the ear, but were also designed to cater to the eye, mainly by way of using beautiful illustrations and gothic letters. An equally intriguing feature of balladry that came up during the seminar was the way in which ballad sellers would use visual effects when promoting their wares. Jeroen Salman showed examples of “songs on cloths”, i.e. how peddlers of the Netherlands would use canvases with visual representations of the theme of the ballad in order to sell their wares in markets and busy streets. Salman has worked extensively on transnational peddling of popular literature, with a particular focus on the Low Countries, and it was interesting to see how the “songs on cloths” was paralleled in David Hopkin’s presentation of French ballad pedlars who also used this as a way of selling ballads as well as other types of literature. Swedish scholars have found examples of the same devices, so this feature promises to be one amongst several interesting comparative aspects of European ballad culture. Meanwhile, some of Alison Sinclair’s examples of Spanish ballads were so richly illustrated that they appeared like cartoons with emphasis on imagery rather than text, as is also seen in German broadside ballads.

Into the digital era: What is the future of ballad and news studies?

The last session of our seminar was a roundtable on digitisation and databases of ballads across Europe, with Matthew O. Grenby as chair. Giles Bergelgave us an introduction to digital ballad resources, pointing to what he sees as the three most important questions that should form the basis of the making of digital ballad resources: what does it (or should it) contain; what can you do with it; and who is it for? In his talk, he pointed to the differences between, for example, collections of original materials, catalogues, and Indexes and bibliographies, and he showed us examples of archives across Europe.

Lively discussions on digitisation and ballad databases, chaired by Matthew O. Grenby and with an introduction by Giles Bergel.

The roundtable participants were Astrid Nora Ressem, representing the National Library of Norway, who talked about the importance of cataloguing the metadata and the key role of libraries have in terms of preservation; Jeroen Salman who is the director of EDPOP (European Dimensions of Popular Print Culture) was particularly interested in the possibilities of multilingual, cross-national databases. In the panel was also Angela McShane who has written a game-changing article on the upsides and downsides of digital ballad archives, and Una Mcllvenna who has recently published an Omeka pan-European database of execution ballads. One of the issues that came up was that of endurance: Mark Philp and Angela McShanementioned the problematic aspect of longevity in digital projects that are reliant upon temporary funding, and which risk becoming “ghost-sites” when the funding runs out.

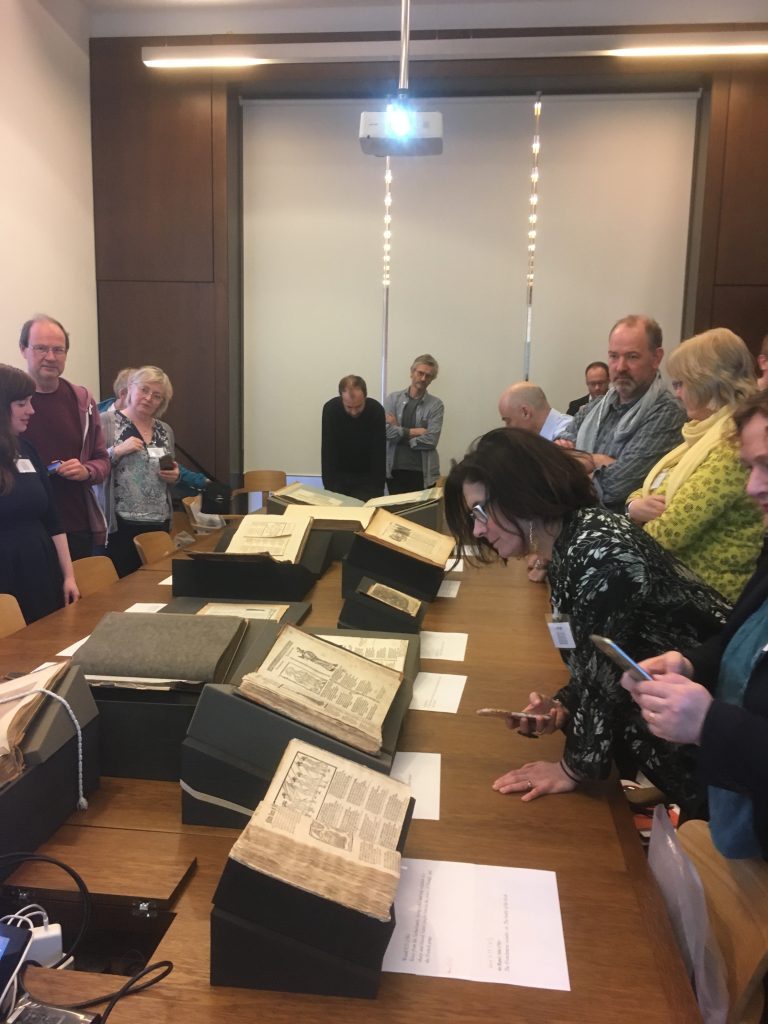

The smell of a ballad: items for display and a visit to the print press of the Old Bodleian

We agreed that digitisation and databases are enabling and enhancing ballad studies in fantastic ways – but this does not mean that we should forget the physical items themselves. In fact, perhaps digitization and the increased strictness of libraries in allowing access to the physical material which has followed in its wake has created a more prominent urge amongst scholars to see, feel and smell the items themselves. For that reason we are deeply grateful to the Bodleian library for facilitating a display of many treasures from the history of ballads in our seminar room. This small exhibition deserves its own blog post, but for now we can say that the items displayed – which I was allowed to choose especially for the seminar –showcased 400 years of balladry, in various formats; from the small, loose leaf chapbook news ballad of the nineteenth century, to the Tudor and sixteenth-century ballads pasted into preciously bound volumes, such as that of the Wood collection.

British new ballads from different periods and in different formats displayed in the Horton room at Weston library, Oxford

Thank you so much to Alex Franklin of the Bodleian for facilitating this. We are also grateful for having been invited into the print press room of the Old Bodleian library across the road from the Weston library, where we were allowed to see and test out print presses from various periods.

Alex Franklin in the print press room at the old Bodleian

Upper case and lower case. Some Norwegians – we won’t not mention who! – had a linguistic revelation this day

…and then there was singing!

No ballad seminar is complete without examples of the aural function of balladry. I had asked Anne Sigrid Refsum and Jenni Hyde to sing excerpts of a Norwegian and a British news ballad respectively, and during pre-dinner drinks in Jericho, the two renowned singers gave us the perfect ending to an interesting day. The clips below give little credit to the performers – such things must always be experienced live – but I nevertheless include them here in the hope that this important side of ballad culture can form a part of collaborations in the future.

Anne Sigrid Refsum

Jenni Hyde

Sweden, hello, can you stand still please… Spain, hola?! Stop fiddling with your hair, Norway…France: please stand further to the… Mon dieu! Deux points! England: Yes, twelve points! A selection of the seminar delegates gathered outside the Radcliffe Camera on April 1, 2019.