Was there a tradition for singing the news of natural disaster in the Czech lands, and if so: What kinds of disasters? They don’t have a coast line here, and the weather conditions were, and still are, fairly balmy compared to, say, Norway. And how catholic were the Czech disaster songs? Did they interpret the disasters very differently from the Scandic, Lutheran ones? And what about that tiny format of their songs – surely there wasn’t much room for long texts or illustrious images?

These were some of the questions that kept me busy, as the bus from Vienna drove into Brno central station, on a late Tuesday in October. I was relieved to have found the right bus in an obscure station miles away from the airport. I was also glad to have my father by my side, joining me for five days of academic larks in Brno. The visit here was part of the first stage of an investigation of disaster songs as a European, transnational genre. In September, I applied to HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area), gathering a team of 16 European researchers. I am also aiming to apply for the impossible-to-get ERC consolidator grant in December. Two project applications within a few months is not my normal academic drill: I haven’t applied for external funding since 2018, and as is the case with most of my colleagues, applications is not really what I want to be spending my precious research time doing. But then I finally have this fantastic topic that no body has really studied en masse before! And these fabulous collaborators! And now, also, the chance of traveling to look at some songs.

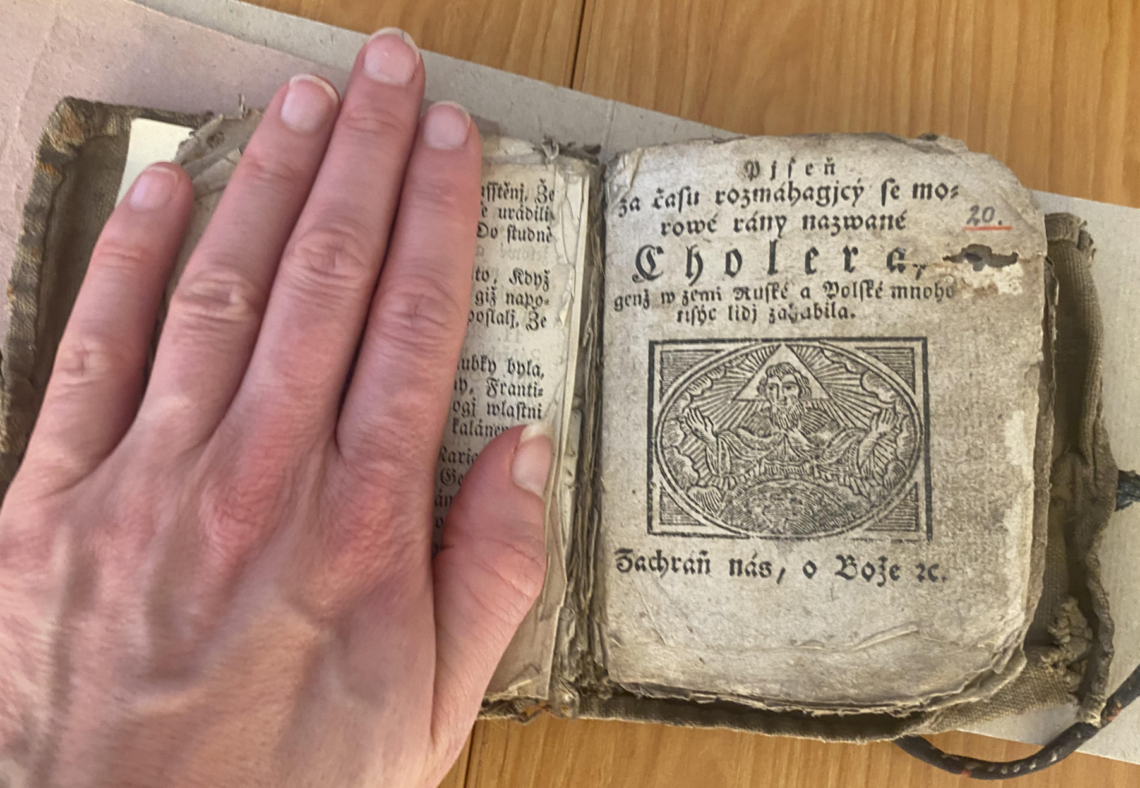

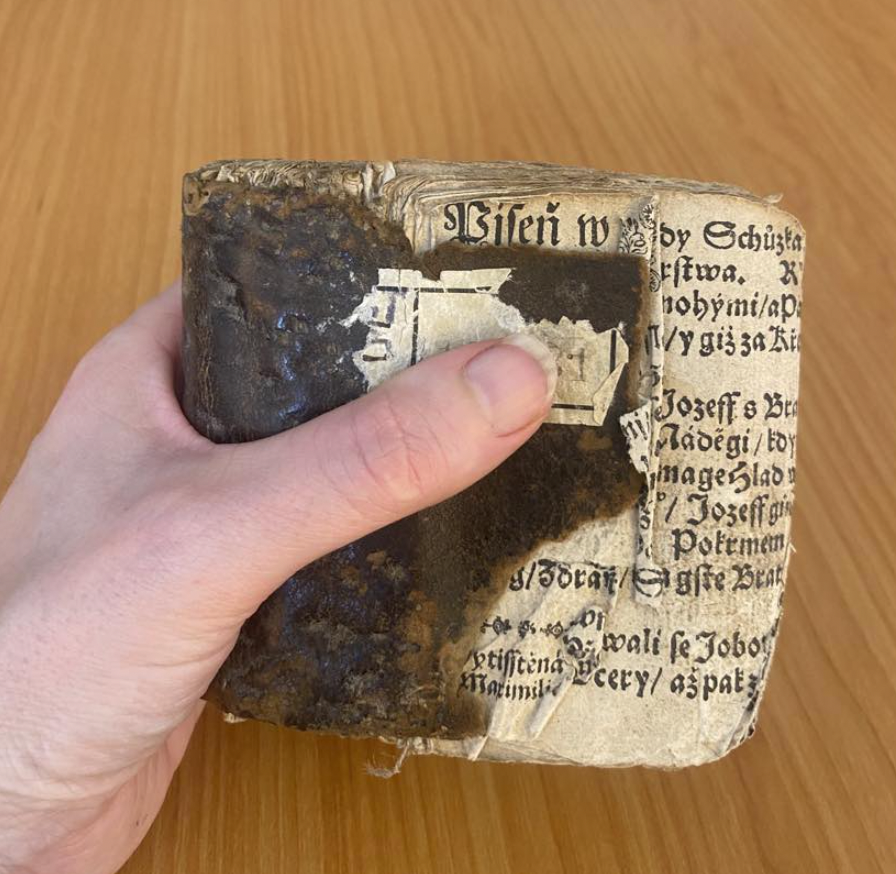

Brno was an obvious starting point for a first probing of the disaster song tradition in a central European context. Brno is, I dare say, the main hub for studies on printed historical songs in all of continental Europe: Since 2018, professor Pavel Kosek and associate professor Marie Hanzelková at Mazaryk University has been in charge of a major research project on Czech songs, resulting in an impressive number of research articles, exhibitions, and a huge book (2022) edited by Pavel, Marie and the director of EBBA, Patricia Fumerton. I was invited to Brno for their concluding conference last year – you can read about this visit in a previous blog post. Marie has since then been to visit me in Trondheim. The bonds between our research projects are already formed, and so I was very pleased to accept an invitation this fall, to do a guest lecture on disaster songs, for staff and students at the Faculty of Arts, Mazaryk university. Particularly since we were also planning to have a first look at the collection of Czech disaster songs from the Moravian Library. Finally, I was once again going to hold in my hands the unforgettably sweet and precious kramářské písně: The tiny and unique sextodecimo prints, measuring less than a fist, but significant for their major tradition of popular singing in the Czech lands, from the 17th to the 19th century.

Our archive meeting at the library was led by Jiří Dufka, who is the head of the department for manuscripts and early printed books. The meeting also included Marie and Pavel, as well as Martin Drozda and Anna Grůzová. Jiří had very kindly found the most important kramářské písně dealing with the theme of natural disaster in their rich collection.

Marie Hanzelková, and Jiří Dufka. And, in front, the protagonists: kramářské písně on natural disasters.

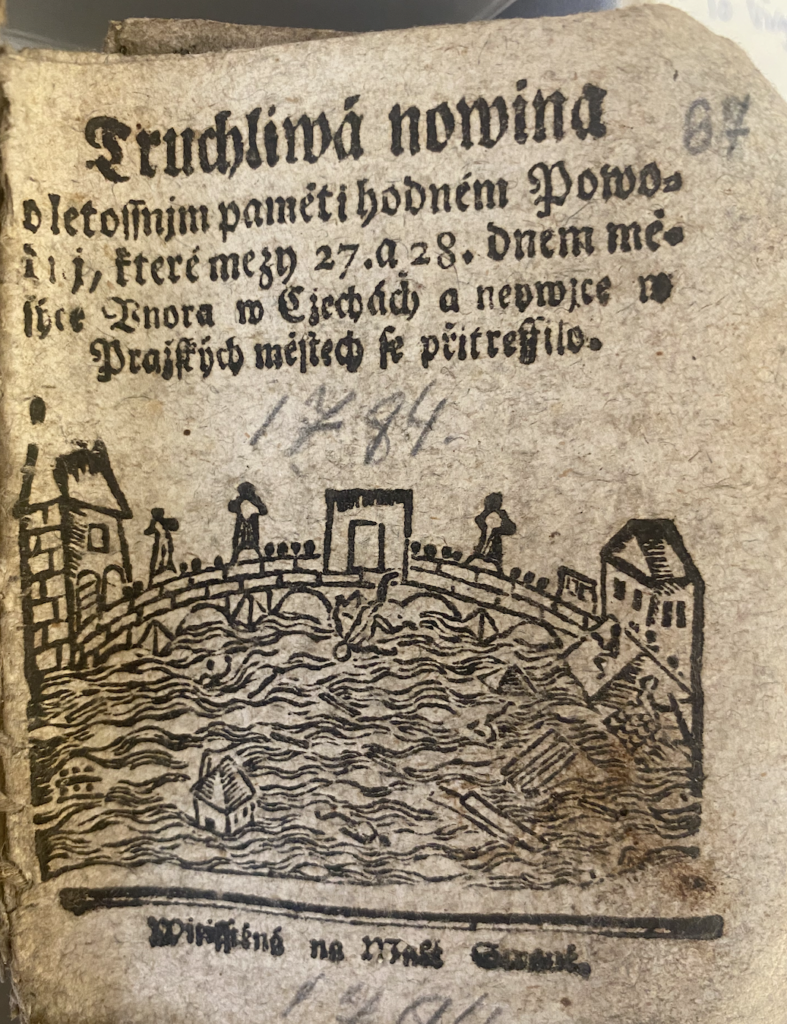

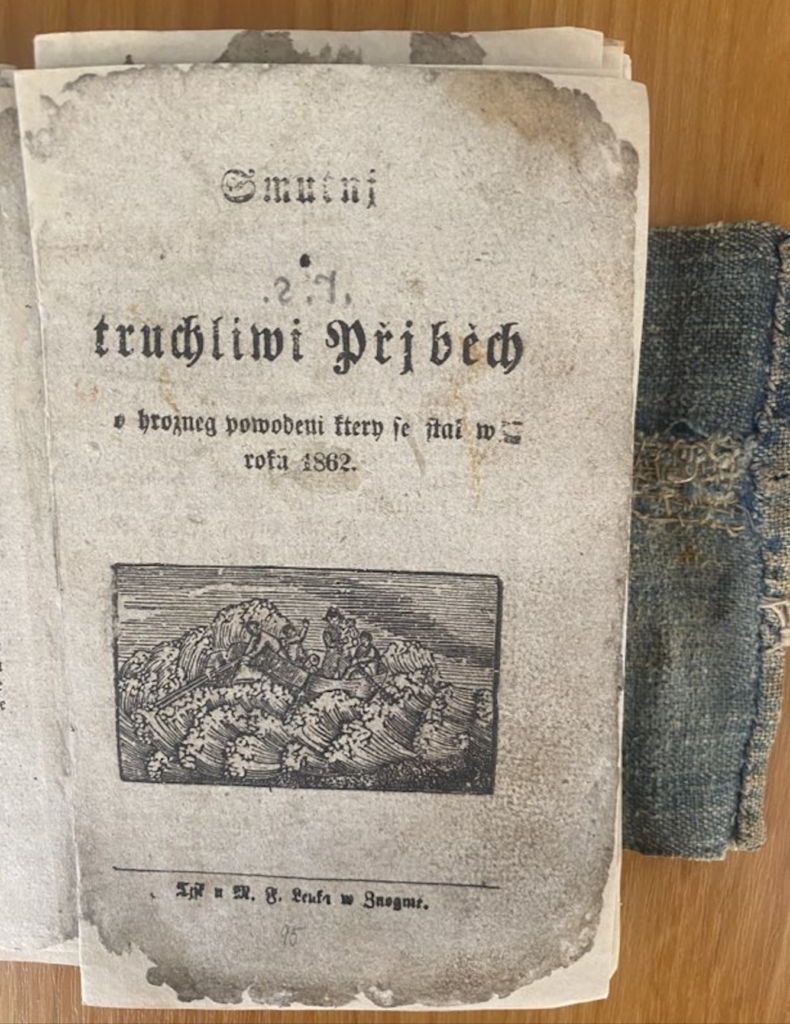

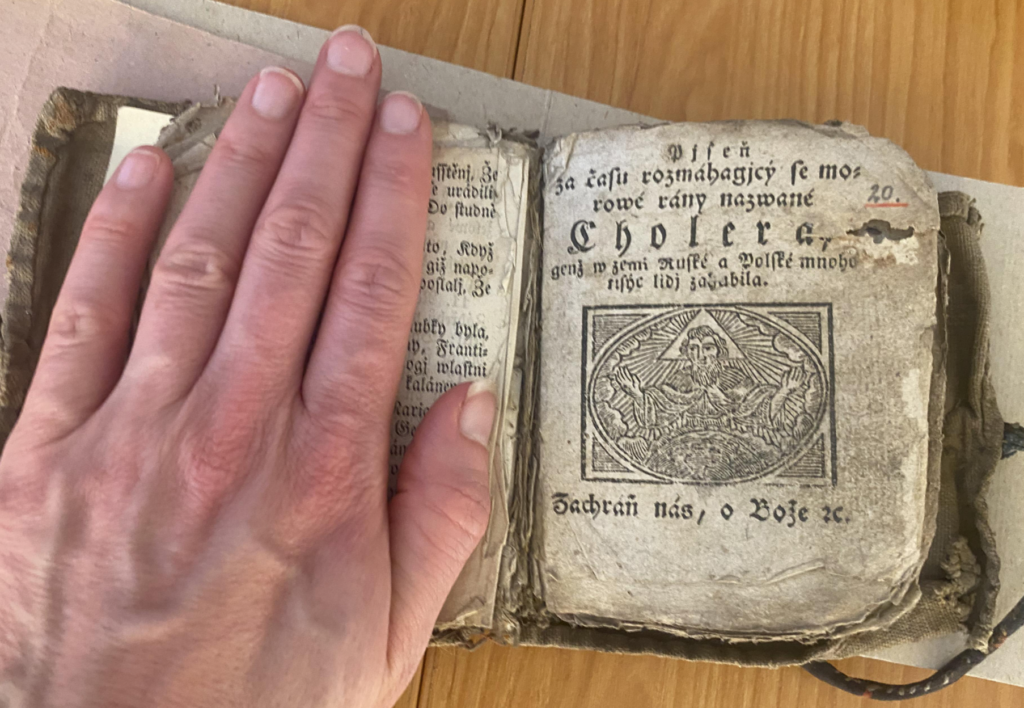

The songs Jiří had brought up from the archives turned out to concern many different types of disasters: Earthquakes, fires, storms, draughts, cattle plagues, cholera outbreaks, and volcanic eruptions. But the dominant type of disaster described in Czech songs is, unsurprisingly, floods. Those majestic and beautiful rivers that flow through multiple countries in central and eastern Europe have done (and are continuing to do) a lot of damage. Jiří has found approximately 250 flood songs, of which between 20-30 songs are unique prints. The songs describe historical floods in the Czech lands and beyond: In Prague (1784, 1845, 1872, 1890), Bohemia (1781), Silesia (1736), Tarnów (1850), Budapest (1838) and in other regions of Hungary (1879), to mention but a few. Some of the flood songs are illustrated with detailed woodcuts, showing people, goods, bridges and houses taken by the water.

The oldest disaster song found thus far is on a storm in Hamburg in 1685 (translated from German). A number of cholera songs from 1866 connects cholera outbreaks to the Austrian-Prussian war. There are also songs on floods in America (1889), and earthquakes as far away as Ecuador (1889). According to Jiří, some of the disaster songs reporting from America appear to be expressing anti-emigration sentiments, e.g. encouraging Czech citizens to refrain from emigrating. If so, this is an interesting example of how disaster songs could be political, nationalistic and propagandistic.

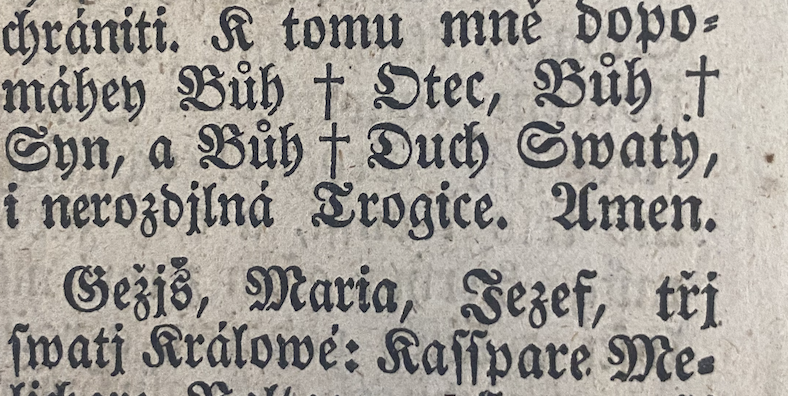

The Brno songteam have, of course, yet to close read, transcribe and translate all the Czech songs – this is what we are hoping to do in the future, when we – if the European funding bodies support us – start digitizing, cataloguing and comparing disaster songs across Europe. Thus, we spent most time with the paratexts, e.g. the title pages, to get an overview of the corpus of disaster songs. But we opened and read some of the songs, discovering intriguing features that may be unique to the Czech disaster song tradition. For example the appearance of specifically catholic textual and typographical features, such as crosses scattered along the lyrics of a song on a whirlwind and storm near a Czech town.

According to Anna Grůzová, who specializes in magical incantations, this was probably used as an instruction and encouragement to the buyers of the song prints, that they should do the sign of the cross and pray, so as to avoid future disasters. If so, it is an interesting example of how the disaster song prints could contain performative features related to religious rites, e.g. that they encouraged their listener-readers to act. Maybe this way of inscribing a religious, performative rite adds yet another layer to the multimodality of these songs, in addition to their oral role?

Yet another interesting feature with Czech songs which is potentially related to confession and religious rites, are songs on draughts which do not mention specific incidents, i.e. they are not news songs in the traditional sense. Some of these songs are more general and non-specific prayers to God to end the draught. But in all likelihood, they were connected to periods of crop failures and hunger, and they should thus be included in the corpus of disaster songs.

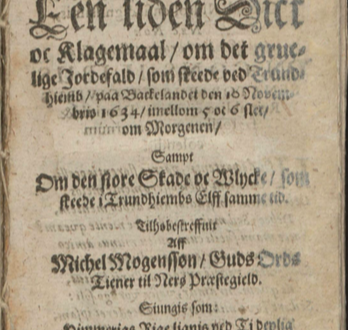

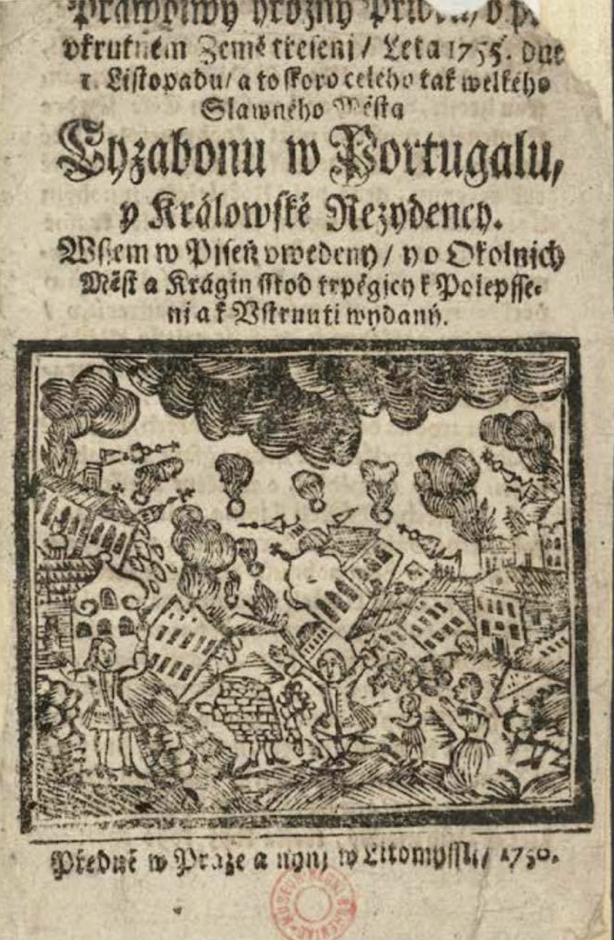

My guest lecture for staff and student was held at the Faculty of Arts, Mazaryk university. It focused on traces of Lutheranism in the earliest Scandinavian disaster songs, e.g. how the cult of remembrance and the fixation on the moment of death that came with the Lutheran disappearance of catholic purgatory is visible in the songs. Heavy stuff, yes, particularly since the lecture was scheduled to last two hours without an interval – this is the norm here! But Marie really wanted her students to learn about Lutheranism, which for obvious reasons is less known amongst Czech literature students. I also presented some examples of how disaster songs display religious-political ‘propaganda’, more specifically I made the case for how the Norwegian songs on the Lisbon earthquake (1755) display schadenfreude, using various literary devices to portray the catholic inhabitants of Lisbon as fully deserving of the devastating disaster that struck on all Saints Day.

With the help of Marie, who had kindly translated to English some Czech songs on the same disaster, we were able to confirm that in this case, confessional proximity to the disaster greatly influenced how it was mediated to a contemporary audience: Where the Norwegian, Lutheran songs on the Lisbon earthquake emphasize the material damage and has little compassion for the people who died, the Czech songs highlight the human suffering, and they are highly emotional outbursts of compassion towards fellow-European Catholics. This contrast is, of course, not a very surprising discovery, but it still needs pointing out. As we start comparing the disaster songs as a transnational genre on a much larger scale, we are likely to find many more of these interesting juxtapositions in what is at heart, I think, the same genre.

The Brno visit coincided with Researchers Night at Mazaryk university, and on our last night my father and I were given our own guide, PhD-student Martin Brezina, and we participated in activities on campus. These included a fun and educational print workshop where we made our own prints on a wood press. There was a linoleum print session too, and my father revived his old skills from his years as a teacher. Marie’s students charmingly performed a bawdy medieval play, and there were stalls with local Czech beer to keep us happy. All the events were captured by a photographer.

Our dedicated tourist time in Brno – the ultimate privilege of traveling researchers – included a visit to the impressive Moravian museum, where several rooms are dedicated to retelling the story of the communist period and the velvet revolution – somewhat of a favorite conversational topic of mine when I am together with my Czech colleagues. The exhibition is highly recommended, particularly if you have a father who was part of a Norwegian radical political movement who fought against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, but which is also remembered for its associations with communism. We also went to the Spilberk castle, nested on top of a hill overlooking Brno. As we were descending the hill, the emergency air-raid sirens sounded. They are used in case of emergencies, including natural disasters. This was, however, just a test; they test them on the first Wednesday of the month all over the Czech Republic. They have previously been used to alert the public to actual natural disasters. What types of disasters, you might ask? I will leave this as a cliff hanger to my next blog post, which concerns another central European country, and their tradition for singing the news of disasters.

Thank you to Marie, Pavel, Jiří, Anna, Martin, Martin, and Zuzana for making the visit to Brno so splendid. See you soon!