On the train from the Brno to Budapest, as part of my 10-day quest for a Central European tradition of disaster songs, I was carrying in my rug sack a small treasure in the form of a copy of a Czech song on a major flood in Hungary in 1838, translated for the first time into English. This was exactly what I was hoping this project could do: Connect various European traditions of disaster songs in a network; to prove that printed songs can shed light on how our European forebears used songs to cope with natural catastrophes; to show how singing the news of disasters was a shared, pan-European practice. I was looking forward to showing it to my soon-to-be Hungarian colleagues. Look, they sang about your Budapest flood in the Czech lands back in 1838 – how does it compare to your own songs on the flood, if you have any?

I was to stay for six days in Budapest, following four wonderful days in Brno. Prior to the academic program, I had a whole weekend as a tourist in the Hungarian capitol, together with my father, a fine traveling companion. We did those things that tourists do here: Get the currency conversion wrong. Eat too much goulash soup. Misunderstand the shower cap rules in the Géllert bath. Tip too much or too little in taxis. Search for food shops selling exciting, local produce and end up shopping in Lidl, etc.

Most tourists coming to a new place will be looking for something unique – something they discovered by themselves, beyond the trodden paths. I am one of these, but I rarely find whatever it is I am looking for, and I most often end up just following the crowds, assuming this and that sight is popular for a reason, right? But in Bn Budapest I did find something, thanks to my bizarre, possibly morbid – but most certainly job related and therefore, as I like to think, purely professional – interest in cultural responses to historical natural disasters. As it turned out, the Czech song I had brought with me from Brno wasn’t just one amongst many song prints reporting from the flood-stricken capitol of Hungary. It was on the flood, commemorated with monuments and plaques all over Budapest. But more on that later. First: The song.

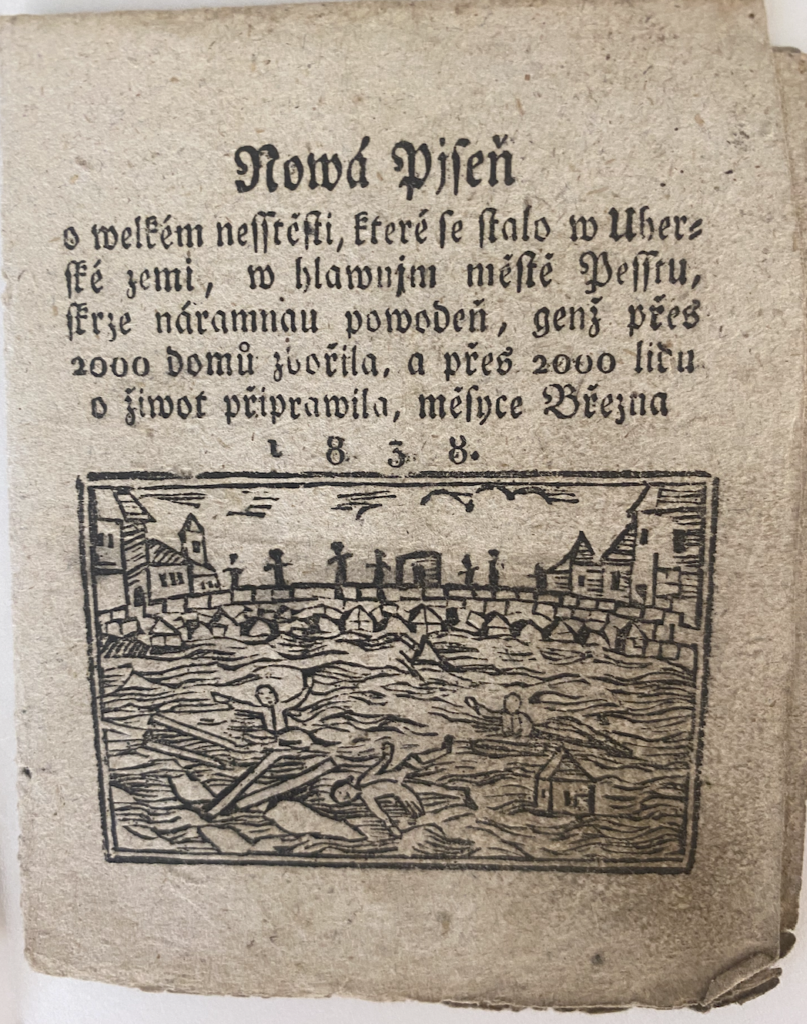

«What misfortunes have happened in the city of Pest»

The title page of the song that the Czech ballad team found in the Moravian Library a few days earlier reads A new song about the major disaster that happened in the Hungarian country, in the capital Pest, through a great flood, which destroyed over 2000 houses and took the lives of over 2000 people, in the month of March 1838. The death tolls are vastly inflated: Although this was one of the worst floods in the Hungarian capitol, it claimed 153 lives, not 2000. The song is written before the separate towns of Buda and Pest (and Óbuda) were unified in 1873, hence «Pest» in the title, which also highlights which of the then-two towns that was worst affected by the flood.

The woodcut is probably not unique. In the Moravian Library in Brno we found an earlier, eighteenth century flood song with similar images. But you can understand why the producer of the 1838-print wanted to (re)use it: Although the woodcut is crude and simple from a modern perspective, it illustrates the drama and misery of a flood, showing buildings and people drowning in water.

The opening stanza of the song is what we call a minstrel strophe in Norwegian – an invocation of an audience – (from wandering minstrels in medieval times), and the subsequent stanzas are informing the audience what has happened – as well as ordaining what they should feel about it:

Oh, have mercy, Christians,

listen to the terrible things,

what misfortunes have happened

in the city of Pest.

It was just the month of March

the waters rose up

at that time there was a fair in Pest,

hear what happened.

The water came to the market,

taking everything in its stride,

goods, people, houses too,

everyone must weep.

The translation cannot, of course, give credit to the actual poem, its rhymes and rhythm, its songfulness (if indeed the original, Czech song has this quality). But we can at least get some idea of the content and the literary imagery. And we can see that in the 26-stanza song, the author wants to detail the event, using a simple technique common to many disaster songs: Zooming in on select scenes of misery, and on small groups of people.

At one house, a master and a mistress

stood with four children,

crying for help for God’s sake,

and there was no help to be had.

People were floating on water

drowned, even alive,

crying sadly for help,

they could not be helped.

People also saw,

how one poor father,

two children on his back,

sat on a piece of ice.

In one sudden moment,

the ice tipped over,

the father and his two children

was immediately hidden under the water.

People also saw

the cradles with the children flowed,

for the water came suddenly,

there was nothing to save.

The author is highlighting the sufferings of children and parents – always the most fragile in disasters – in what we might assume is a sensationalist and overly dramatized tale of what happened these days in march 1838. The main aim of many a disaster song (but not all!) is to arouse strong emotions and compassion in the audience. But the depictions also correspond with drawings and other types of contemporary visual representations, where we see people drowning in water or trying to save their lives by climbing on to rooftops or clinging to ice floes.

It was these same ice floes which caused the disaster in March 1838. After an unusually cold winter where the Danube had frozen over, the warmth of spring led the river ice to collapse, and water levels rose quicker than normal. Ice floes clogged up in the riverbed between Buda and Pest, blocking water from taking its normal turn. On March 13, a dam broke, then another, and the river overflowed the city, turning the streets of Pest into Venice, but without the boats and infrastructure to deal with the water.

It is exactly this kind of chaos and destruction that the Czech disaster song is trying to capture. But no matter how detailed and dramatic its scenes: A historic song cannot really recreate for us today the full magnitude and scale of the catastrophe. Of course, you had to actually be there to understand how high the water rose. However, in the streets of modern day Budapest they have managed to bring this part of their history to life, by erecting monuments to commemorate the flood. Some of these monuments were made when they reconstructed and rebuilt the town after the flood, which is quite moving: It tells us that they were thinking about future generations, hoping that they wouldn’t forget the disaster, if they thus made it part of the public sphere. Most of the monuments show a hand or an arrow pointing out the water levels, sometimes they are chest-high, sometimes way above head height. Without really planning it, I explored these monuments by following the route of the flood, e.g. starting with the monuments close to the Danube River, and then moving deeper into the districts of Pest to look at the plaques located more than one kilometer away from the river. Like this, I came closer to realizing the scale of the flood, seeing how high even the monuments far away from Danube were placed above the ground.

I wasn’t an academic if I didn’t experience a pang of shame and embarrassment, when I realized that in my eager and energetic disaster plaque hunt I came pretty close to what is nowadays referred to – and frowned upon – as dark tourism: The seeking out of sights involving atrocities, disasters and human misery. I wasn’t exactly doing smiley selfies in front of mass graves. No, I was being a serious literary historian, aiming to compare the different mediums of commemorating disasters. But as I was filming the most spectacular monument – the Belvárosi Ferences church relief – moving my camera back and forth between the Erzebet bridge and the relief – I realized that I was lowering my voice, probably for dramatic effect. And as I stood there on the busy sidewalk for quite some time, I was inevitably joined by some other tourists, bewildered as to what I, and no also they, were looking at. And so it was, that I had my debut as a dark tourist guide. “Have you ever head of the 1838 flood….?”

The only comfort of this sorry tale is that by showing such an interest in disturbing stories, I was illustrating one of many connections with our European forebears: People have always been intrigued by disasters, and not always for the most morally acceptable reasons. The Budapest flood song has some particularly goory details, as a sort of morbid finale:

Those who were not drowned,

would have starved to death,

for they could not grind, nor bake,

the water took all the mills.

One man escaped

in the flood on the roof,

and a great hunger overtook him there,

for he was there till the fourth day.

Hunger must be a very hard thing,

so this man can testify,

for he had to eat flesh from his own hands,

that he would not starve to death.

The tale of the man eating his own flesh might not be genuine, indeed it sounds a bit far fetched. But after years of investigating disaster songs, I have learnt not to assume that because it’s macabre, it must be fake, not even with tales involving cannibalism.

Temples of knowledge

After my brief career as a dark tourist guide, I was ready to resume my normal academic pursuits, and to give my lecture at the university. Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE for short) was founded in 1635, and it is one of Hungary’s largest and most prestigious universities. Here I was finally to meet my main Hungarian collaborator with whom I had thus far only met online. Emese Ilyefalvi is an associate professor at the Institute of Ethnography and Folklore. She welcomed me at the main gate of the humanities campus, located centrally in Pest, and forming a labyrinth of beautiful, old brick buildings adorned with leafy trees.

As is the case in the Czech Republic, you are treated as a highly distinguished guest when you come here as a visiting researcher – a strange and funny contrast to the general brusqueness in the public sphere, e.g. in shops and restaurant. Hungarians are, then, a bit like Norwegians: Warm and welcoming to insiders, cold to outsiders. My ticket to Budapestian warmth was that I was giving a guest lecture, which was attended by a flatteringly high number of staff and students. Like my lecture in Brno, this one was also to last for two hours with no interval – this, I gather, is the Central European way. But the students were amazingly energetic, asking interesting and challenging questions to my presentation, which revolved around both the Norwegian and the European tradition of disaster songs.

Emese gave me a tour of the campus, and we saw students lounging in bean bags, with coffees, beers and books – a beautiful sight. Is this town, or at least the academic bit of it, in fact a hot spot for that old-fashioned, near-extinct thing of reading books? The area where I stayed was dotted with antiquarian and second hand bookshops. There was even one right outside my flat. And in the park behind the flat there was both a free library cupboard and a book-automat for those who absolutely need a book outside shop opening hours. Someone told me that Hungarian readers still prefer physical books to e-books. But I am wondering whether there is also an old-fashioned appreciation of bookishness here – a valuation of the written word, of intellectualism, of the academy –attitudes which I have only encountered in academic hubs like Oxford and Cambridge. But I might have been romanticizing things, as I often do. The low salaries of academics in Hungary, as well as Orbán’s efforts to destroy the education system and all other good things this country has to offer, suggests as much. And yet: When Emese and I went to look for disaster songs at the University Library – a grand, enormous building located in the same street as my flat – I realised that this was the art noveau building my father and I marveled over on our first day here, when a low evening sun made the yellow dome look like a cathedral. The insides of the library was no less magnificent. A quirky temple dedicated to books and knowledge – and with a small but interesting archive of disaster songs.

The day after, as I walked over the Széchenyi chain bridge from Pest to Buda and climbed up Várhegy hill, I realized that the National Library I was heading towards, is actually part and parcel of the ridiculously grand Buda Castle, the royal castle which dominates the hillside. And I felt that thrill which I always feel in Oxford: Ha! This is exactly how beautiful a library should be, and it should be located in the heart of everything, no other place is good enough. Hey, why not – what we are doing as academics can be likened to the workings of kings and statesmen!

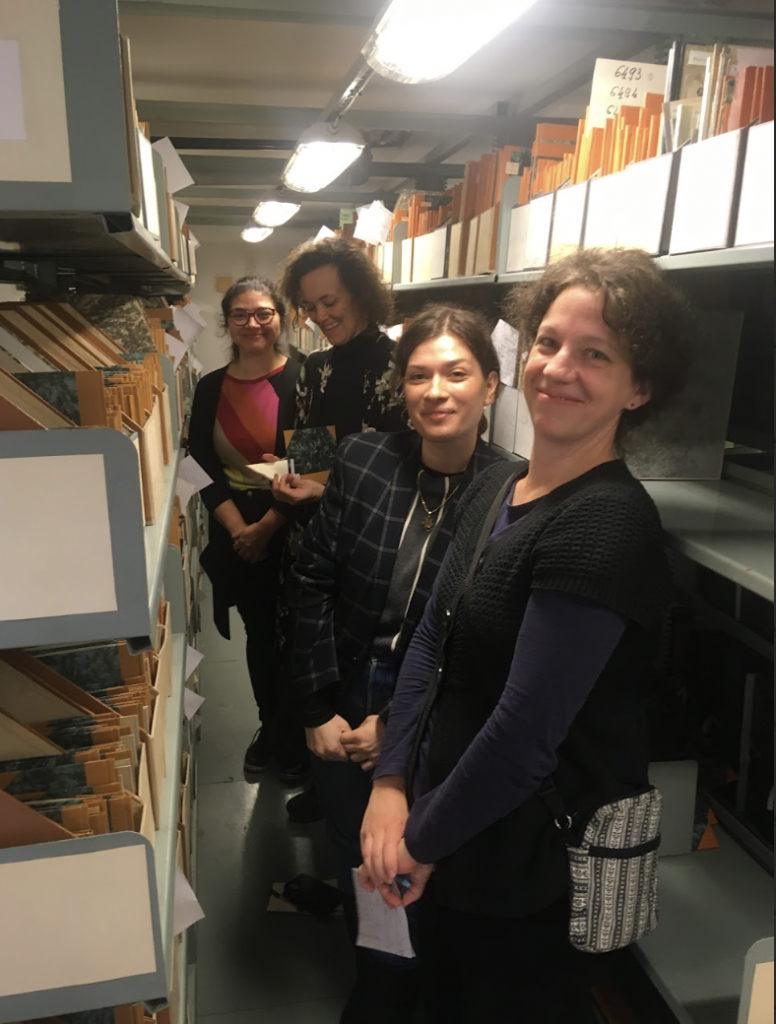

Archives of song

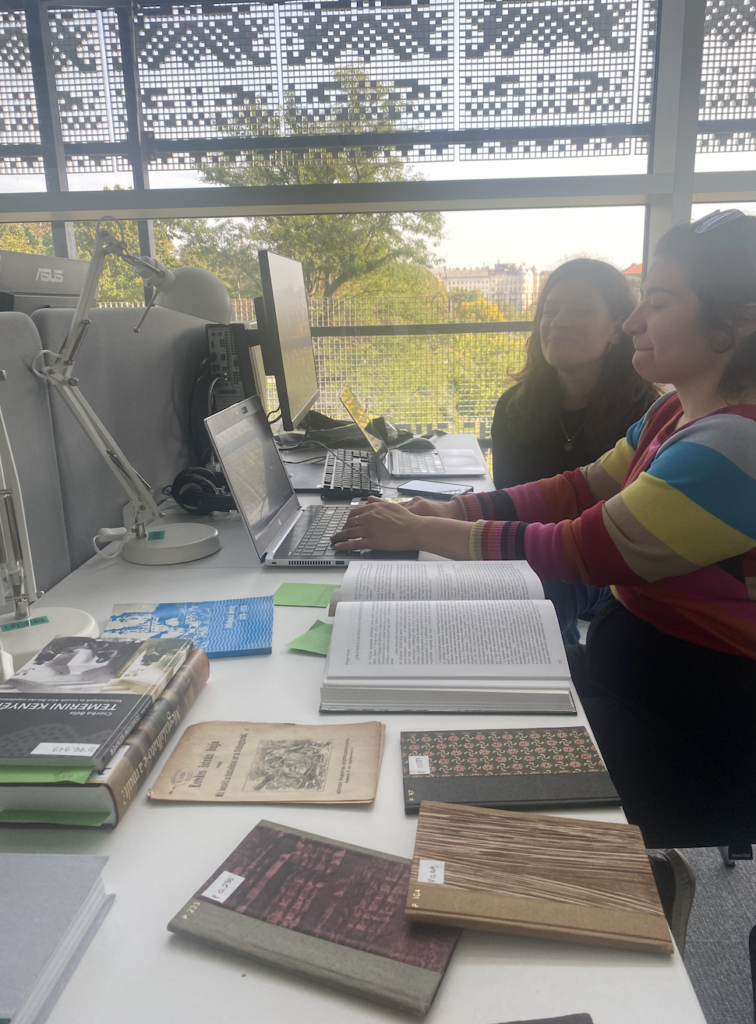

I was met outside the National Széchényi Library by Emese and PhD-students Szylvia Bobak and Judit Chikány. They had kindly set aside time to be part of this first stage of mapping the Hungarian disaster songs. Emese had spent considerable time finding and preordering items for us to look at in the special collections for old prints and posters. We were even allowed down into what for any scholar interested in old prints and books is the ultimate candy shop: The archive where the material is stored. This gave us the first pleasant surprise, namely that the prints are beautifully stored and restored, all of them bound in acid free paper binding, and neatly kept in boxes. This means that they are safe from folds and tears, and the paper is not deteriorating as in so many European archives.

Our preordered items were waiting for us in neat piles at a table in the upstairs reading room. We divided the piles between us. I took the smaller pile of German songs, and throughout our little workshop I was given snippets of translations from my three collaborators who were browsing through the Hungarian songs. This is a song on an earthquake, oh gosh the gory details! This is an emotional song about a flood. Oh, dear, the rhymes… Many of the disaster songs were equipped with illustrations images, enabling me to understand some of the contents without knowing the language. We were not allowed to take pictures of the actual songs, so you just have to imagine what they are like –until, hopefully, one day (if funding allows!) we can catalogue and digitize them for all to see.

Most of the songs are catalogued as ponyva (see below), but this category also holds chapbooks and almanacs – the latter was a particularly popular type of Hungarian cheap print in the eighteenth- and nineteenth century. Emese is trying to get an overview of the material in different Hungarian and Austrian archives, and the quest for songs is an exciting albeit time consuming endeavor. To further complicate matters, many of the assumed song prints she has ordered up from the archives are, in fact, prose-only texts. There is also a type of “narrative in verse”, which was probably read out loud, but we do not know whether they were also sung, since there is no indication of melody. For now, we include these in the corpus of disaster songs. Best to be inclusive during this first phase.

Emese also shows me that Hungarian historical print songs are not united under one generic term; rather, they come with a terminological diversity which makes them even more tricky to find in archives. Énekek and dal are the most common generic terms to appear on the title pages, both words meaning song. Énekfüzet is a song booklet, a collection of songs. Nép dal, Emese tells me, means folk song, and hírsvers means news song. A particularly interesting term used on cheap print and songs is ponyva, a derogatory word referring to the cheap canvas fabric that these songs were laid out on when sold in fairs and markets in the eighteenth century (If you google ponyva you get images of modern-day plastic tarpaulins!). Perhaps the commercial connotation of ponyva connects the Hungarian song tradition to the Czech kramářské písně, the Scandinavian skillingsviser, and the English chapbooks – all belittling terms added in hindsight, to define these songs as cheap and commercial literature.

The prints Emese has found show that there was indeed a tradition for disaster songs in Hungary, and it is more international than we could have hoped for. There are songs on foreign earthquakes, for example in Ischia, a fire in Philadelphia, and songs on the volcanic eruption in St. Martinque (1902). There is also the only song I have seen so far, on the China flood of 1888. The Yellow River flood is history’s second largest natural disaster in terms of death tolls. A German song about an earthquake in Hungary in 1763, printed in Budapest, mentions the Lisbon earthquake, revealing an important feature of disaster songs in the early modern period: the sense of “global” connectedness that has little to do with climate, and all to do with religious interpretations of disasters as God’s wrath and His widespread punishment for the sins of men.

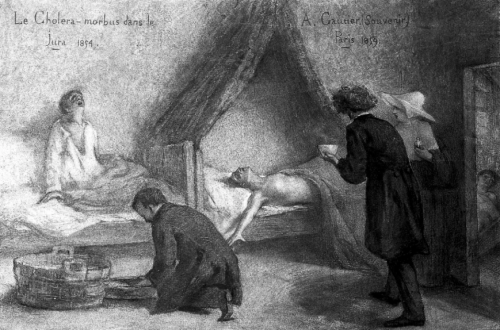

There are Hungarian songs on domestic disasters too, of course, for example a song about a storm on Danube capsizing a boat (1900), and several songs on floods in Budapest (including the 1838 flood), in Szeged, on the river Tisza, and in other Hungarian regions. There is a fair amount of songs on cholera (1831, 1866, 1874). In a long narrative verse (possibly a song) from 1892, cholera is personified as a person walking down the street, engaged in a dialogue with the people he meets, telling them how many he will kill per day. The text is also educational in a way that sounds eerily familiar in post corona times. It contains advice about how to not get infected: Keep a distance, wash your hands with soap and drink good wine!

Amongst the most interesting Hungarian disaster songs are the types dealing with locus swarms, portraying the crop-eating insects as evil “armies”. The oldest one Emese finds is a 1749 song on a locus swarm attacking Hungary, Transylvania and neighboring countries in 1748. The youngest locus swarm song is from 1904. An even more regional type of disaster song is a kind dealing with the grape disease phylloxera. We can probably classify most of the songs detailing how diseases and insects affected crops as famine songs, since several of them deal with the dramatic consequences for farmers and for the public. In a song about an icy hailstorm in 1898, we hear about how the frosty weather destroyed crops that year, leaving people with nothing to eat.

Johnny Depp, Al Pacino, eight sheep and a goat

After long days of archival work, as I came into my flat one evening – a wonderful place full of rustic charm in the center of Pest – I noticed that they were finally packing up the trucks with stuff in the streets outside. For two days and nights, the otherwise peaceful street had been buzzing with activity, as they were shooting a film right outside my windows, next to an antiquarian book shop. This wasn’t entirely surprising: I had already learnt that Budapest is a popular location for shooting films, both because it is so picturesque, and also because it is (still) cheaper to do a film here, compared to a number of other European cities. A few days earlier, my father and I also found ourselves caught in the middle of a Bollywood production during our river cruise (If you watch the upcoming film: Look for the grey-haired man with arthritis with a youngish woman by his side, wearing a jacket dirty with goulash spots – an item rarely seen in such films). I don’t know much about making films, but I quickly realized that the one that was in the making outside my flat was not a Bollywood production, but something much bigger and costlier. Truck after truck with people and props kept on coming, and posh cars with blackened windows too. And on the second night: An ever-growing amount of onlookers, e.g. people just standing around waiting for hours, for something – or someone.

On the night before I was doing my lecture, it was also getting increasingly noisy, and in a fit of academic self-importance I wanted to shout out the window: “Excuse me, could you please keep the noise down a bit? People are trying to prepare a lecture on the transnational praxis of singing the news of disasters circa 1550-1850 here!” But at that moment I started hearing loud yells, for “Johnny, Johnny”. And so comes a moment in the life of any academic, when one needs to put the Mac down and be a paparazzi photographer in pyjamas, documenting the famous actors shooting a film right outside ones bedroom window.

I didn’t get much sleep that night – after Johnny Depp and Al Pacino and whoever had left the building, came a large team of people clearing up the mess and props, including herding a bundle of noisy sheep and one particularly loud goat, into nearby vans. But at least I was able to start my lecture the next day with a sentence I am unlikely to be ever repeat again: Apologies if I look a bit tired, I was kept up last night by Johnny Depp, Al Pacino, eight sheep and a goat.

Thank you to Emese, Szylvia, Judit and students and staff at ELTE for thrilling days in Budapest, and for making me feel so welcome. I am looking forward to our further collaborations on the Hungarian and European tradition of singing the news of natural disaster.

If anyone is interested in exploring the commemoration of the 1838 flood in Budapest and you read Hungarian, use this web page, giving the place of more than 50 plaques:

https://dunaiszigetek.blogspot.com/2011/03/az-1838-as-jeges-arviz-emlektablai.html

If you need an English guide, I found this one, with much fewer plaques, but with brief and interesting information about them and about the flood.

If you are a different type of commemorator, a film fan, or a Johnny Depp/Al Pacino fan, who wants to live close to one (of several) locations used in this upcoming film: Write me an email, and I will give you the address of the apartment I rented – a real historic gem of a flat, close to everything Pest has to offer (and with Buda and the Danube River only a short walk away).